The Last Lone Inventor

A Tale of Genius, Deceit, and the Birth of Television

HarperCollins (2002); Perennial Paperback (2003); Audible audio (2020)

One of Amazon’s "100 Biographies & Memoirs to Read in a Lifetime"

The Last Lone Inventor author & story featured on History Channel docuseries “The Machines that Built America” - premiered summer 2021 (watch it here)

PRAISE for THE LAST LONE INVENTOR:

“A wonderful tale, riveting and bittersweet”

“A fascinating and important story”

“One of the 75 best business books of all time”

“A riveting American classic of independent brilliance versus corporate arrogance. I found it more fun than fiction”

“Farnsworth is probably the most influential unknown person in the past century, and Evan I. Schwartz tells the fascinating inside story.”

Excerpt from the Prologue

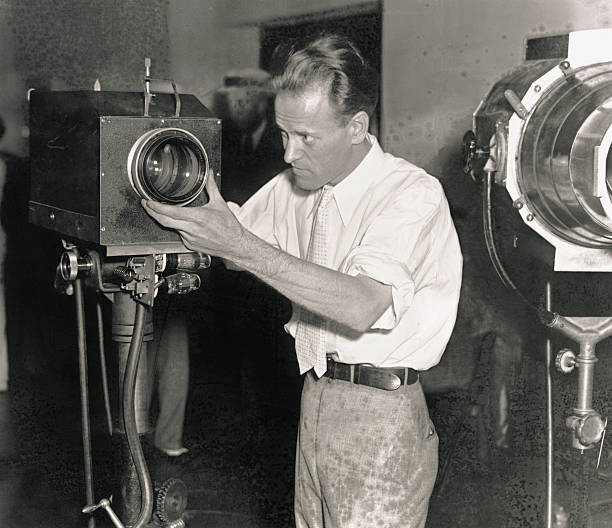

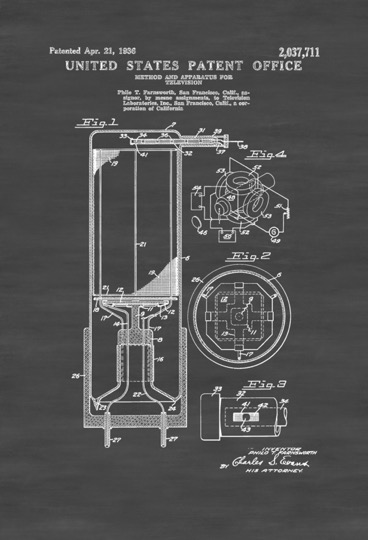

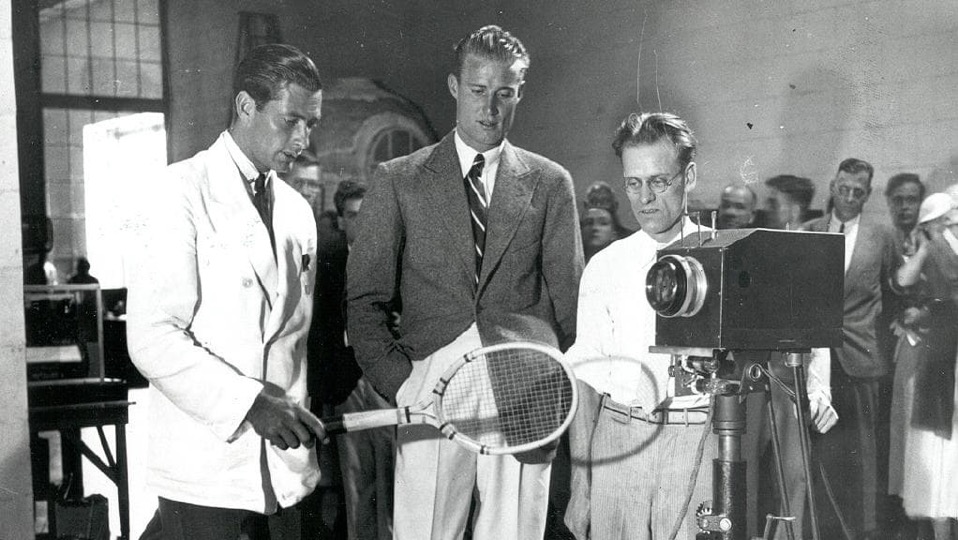

There was a time when Philo T. Farnsworth was the perfect picture of inventive brilliance. On September 3, 1928, a photograph of him appeared on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle, bold type hailing the “young genius quietly working away in his laboratory on his revolutionary light machine.” Just 22 years old, he had recently grown a mustache to mask his youth. His unsmiling expression barely hinted at his inner exhilaration, and his eyes fixed somewhere beyond the lens of the camera, as if to deflect attention away from himself and toward the two tubes he was holding in his hands. The article described these quart jar-sized devices as the first all-electric “sending and receiving tubes of his new television set,” a system that transmits twenty pictures per second, each frame containing eight thousand elements, or pinpoints of light.

The evening the story was published, Farnsworth was driving down Market Street in an open-air roadster, heading back home from an evening at the movies. His 20-year-old wife, Pem, was riding next to him.

Among those most interested in reading the article was David Sarnoff. Sitting at his glass-top desk high up in New York City’s towering Woolworth Building, Sarnoff spent much of his day reviewing and responding to press clippings, reports, and memoranda. The founder of the NBC radio network, Sarnoff had recently been named acting president of NBC’s parent, the Radio Corporation of America, as the actual president had taken a leave of absence to work full time on Herbert Hoover’s 1928 run for the White House. Sarnoff used to opportunity to establish his reputation as the Babe Ruth of broadcasting.

Philo Farnsworth didn’t quite realize that the process of invention itself was being transformed. Innovation became too important and too lucrative to be left in the hands of unpredictable, independent individuals. The giant corporations that had sprung up around all the new technologies of the past century wanted to control the future and avoid surprises that could topple their empires, and they were growing more and more frustrated over negotiating for patent rights.

Both men were bursting with such abundant self-confidence that neither could conceive of defeat. They imposed their talents and their wills, their hopes and their fears, and even the quirks of their personalities on the invention. Out of the confrontation, modern television would emerge, ingesting images of reality deep inside itself, then spitting our reordered flickers of phosphorescence into living rooms everywhere. By the time the inventor and the mogul would die, in the very same year, the number of homes on Earth with televisions would surpass those with indoor plumbing. Philo Farnsworth and David Sarnoff were fighting over something more than just a box of lights and wires.